Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

In 1978, a dredging gang working for British Waterways was struggling with a problem. They were trying to clear obstacles on the Chesterfield Canal so they could stabilise a concrete wall — not an easy day’s work. But what really had them stumped was a heavy iron chain on the canal bottom. After various attempts, they hooked the chain to their dredger. That did the trick. A firm pull removed the chain and the block of wood on the end of it. The gang took a well-earned break for tea.

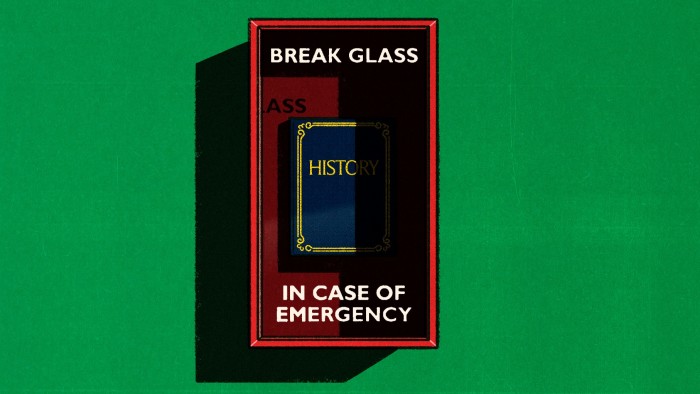

The tea break was rudely interrupted by a policeman in a state of some excitement. He had been passing the normally tranquil waterway when he could not help but notice a large whirlpool. By the time the crew returned to the scene, the canal had gone. “We didn’t know there was a plug,” protested one workman. And, in fairness, the canal was two centuries old, and so was the plug. Whatever records there may have been had been destroyed in the Blitz. The moral of the story: institutional memory is valuable, and if an organisation starts forgetting important matters (such as the existence of the plug) bad things happen.

It’s not easy, though. I was recently taken on a tour of the Bodleian Library’s portrait collection, and was struck by how hard our tour guides had had to work to recover basic information about the sitter and the artist, even in portraits just a few decades old. This wouldn’t be so remarkable, except that the entire reason for the Bodleian Library to exist is to preserve information in an accessible form. (Bodley’s librarian, Richard Ovenden, has written Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge and is president of the Digital Preservation Coalition.) But the Bodleian is a library, not a portrait museum, and without constant attention, the natural order of things is not to remember, but to forget.

That means trouble. Consider Volkswagen’s disastrous scandal, in which the company designed its cars to fool emissions tests by regulators. No, not the scandal of 2015, which cost the company its reputation, its CEO and well over €30bn in fines, settlements and legal fees. I mean the scandal of 1973, in which VW was accused by the US Environmental Protection Agency of designing its cars to fool emissions tests by regulators. VW settled out of court and, it seems, spent the following decades forgetting what should have been a chastening experience.

A more tragic example is the pair of fatal Space Shuttle explosions, Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003. These accidents seem very different. One was an explosion shortly after take-off, the other a break-up on re-entry. But the underlying errors that made them possible seem eerily similar. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board report noted that the same basic questions had emerged: why did both shuttles keep flying with known problems? And why did Nasa managers decide that it was safe to launch despite warnings from their engineers? To set the stage for Columbia, Nasa first had to forget all the lessons of Challenger.

There is more to institutional forgetfulness than forgetting one big thing, whether that is “if you cheat the EPA, they may figure it out” or “the canal has a plughole”. Organisations can also just forget how to get things done.

As a boy I was fascinated by the Lockheed TriStar airliner because of its unusual configuration, with one engine in the tail. You don’t see it much these days — the TriStar was not a commercial success.

I wasn’t the only person to be intrigued by the plane, but the organisational psychologist Linda Argote had a different reason to scrutinise it. Most aircraft get much cheaper to make with the benefit of experience — they are the canonical example of learning by doing. But the TriStar stayed stubbornly expensive to make. Argote wanted to know why. Her idea flipped the idea of learning by doing: what about forgetting by not doing?

In a 1990 article Argote and Dennis Epple concluded that Lockheed had made so few planes they were forgetting faster than they were learning. In particular, in 1977 and 1978 production slumped to just 14 TriStars in total, and by the early 1980s costs in real terms were higher than in 1975.

The economist Lanier Benkard later estimated that Lockheed’s cost-saving expertise tended to drain away alarmingly fast if not refreshed by activity, with a half-life of just over a year. We can’t generalise too much from that. Planes are planes, and every case is different. Still, anyone who has ever filed tax returns can attest that a year is easily enough time to forget how to do any complex process.

Forgetting can happen for many reasons. People leave. Physical archives are vulnerable to mould and fire and being misplaced. Digital archives tend to become unreadable as technology changes — indeed the final reference in the Wikipedia entry on organisational memory is a dead link to a lost NHS website.

And sometimes organisations deliberately forget. The underlying cause of the Windrush scandal in the UK was that one part of the Home Office decided to make onerous demands that UK residents prove they had the right to live and work in the country, without knowing — or much caring — that another part of the Home Office had destroyed the records that made such proof possible.

More than 100,000 US government web pages disappeared after President Trump took office. It remains to be seen what is gone temporarily and what has been lost for ever.

It is easy for organisations to forget, even when they are trying to remember. Let’s not make this worse than it has to be, or it will be more than the Chesterfield Canal that we lose.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram