Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the War in Ukraine myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin

The war between Russia and Ukraine has escalated dramatically in recent weeks. Yet western policy remains anchored in the dangerously misguided assumption that Russia’s economy will crack under the staggering cost of militarisation, anaemic economic growth and decreasing oil prices. President Vladimir Putin has no intention of demilitarising the economy, even if the fighting in Ukraine were to end. The Kremlin aims to make its war machine bigger and better, stands ready to sacrifice ordinary Russians’ quality of life along the way and is unlikely to meet significant resistance.

In 2025, Russia’s military spending will reach nearly $172bn: equivalent to 7.7 per cent of GDP and a 12 per cent increase on 2024. The 2025-2027 fiscal plan locks in this high level — about 7 per cent of GDP — for the entire period, and that is unlikely to change.

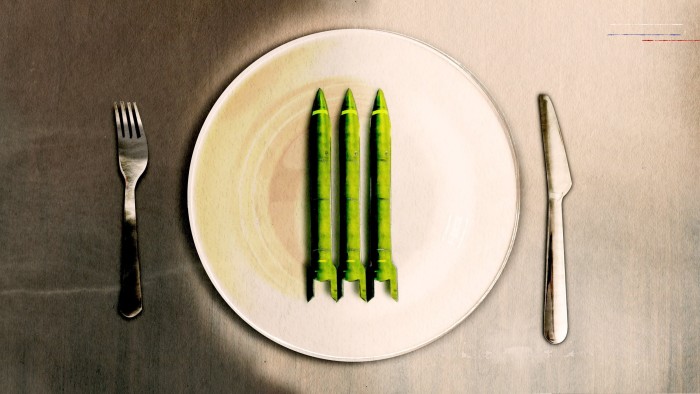

Two major spending lines underpin this effort: the production of weapons and equipment, and payments for personnel on the battlefield. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has doubled its output of armoured vehicles and increased munitions production exponentially. The state-owned defence conglomerate Rostec has opened new plants and assembly lines. A fresh sector — mass drone manufacturing — has emerged. Russia is also managing to get more bang for its buck than Nato; Rostec’s artillery shells cost roughly 25 per cent of German arms maker Rheinmetall’s.

Even if the war were to end tomorrow, equipment production would continue at pace. As the army eats through Soviet legacy equipment, Putin is determined to replenish stockpiles — and equip his military with the most modern kit informed by wartime innovation.

This will take several years, keeping the performance-enhancing drug of high military expenditure in the Russian economic system. The Kremlin is also looking to arms exports to maintain elevated levels of military production and generate cash: Putin hosted a high-level government meeting to that end on May 23.

It has become something of a habit to talk down Russia’s toolkit, but many buyers around the world may take different lessons from its efficient deployment of its homemade hardware. This includes electronic warfare systems that make expensive GPS-guided tools obsolete, and wired drones that Kyiv first mocked and then imitated.

Should active combat subside, the Kremlin has strong incentives to maintain an expanded military and delay the reintegration of veterans into the civilian labour market. While Russia will try to keep its battle-hardened troops in uniform, offering them salaries three to four times higher than those in the civilian economy, the Kremlin will no longer need to pay compensation for killed and wounded soldiers, which currently constitutes the bulk of personnel spending. As battlefield requirements eventually decline, resources will be freed up for further investment in military capacity.

Such spending will inevitably weigh on economic growth. Yet Putin’s focus is not on GDP, but on rearmament. He has already signalled to the government that growth slowing from the current 4.3 per cent to around 1.5-2 per cent would be an acceptable trade-off. In short, Russia is on a trajectory of sustained militarisation. To justify this, the Kremlin can point to the fact that European defence spending rose by 17 per cent last year to $693bn. That trend is unlikely to reverse. “Russia must stay one step ahead,” Putin said at an April military-industrial commission meeting.

Low oil revenues will not derail the economy, but accelerate the shift in spending towards military priorities. What matters for Russia’s budget is not how far oil prices fall, but how long they stay depressed. A $10 drop in the benchmark oil price to $50 a barrel would shave roughly 0.8 per cent off GDP in government revenues — a manageable loss. The planned increase in the federal deficit this year from 0.5 per cent to around 1.7 per cent of GDP is not catastrophic. Reserves are sufficient for 2025. In the years ahead, civilian infrastructure and subsidies will be the first on the chopping block. The government and central bank are actively preparing for a whole range of scenarios.

The notion that Putin is under pressure from his military-industrial lobby to continue the war is fallacious. The initiative comes from the president himself. His overriding strategic goal is to strip Ukraine of the core element of sovereignty as he defines it: the ability to defend itself. If he fails now, he may try again with a bigger military and better arsenal. Appetite, after all, comes with eating.