Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is author of ‘How Progress Ends: Technology, Innovation, and the Fate of Nations’ and an associate professor at Oxford university

Each time fears of AI-driven job losses flare up, optimists reassure us that artificial intelligence is a productivity tool that will help both workers and the economy. Microsoft chief Satya Nadella thinks autonomous AI agents will allow users to name their goal while the software plans, executes and learns across every system. A dream tool — if efficiency alone was enough to solve the productivity problem.

History says it is not. Over the past half-century we have filled offices and pockets with ever-faster computers, yet labour-productivity growth in advanced economies has slowed from roughly 2 per cent a year in the 1990s to about 0.8 per cent in the past decade. Even China’s once-soaring output per worker has stalled.

The shotgun marriage of the computer and the internet promised more than enhanced office efficiency — it envisioned a golden age of discovery. By placing the world’s knowledge in front of everyone and linking global talent, breakthroughs should have multiplied. Yet research productivity has sagged. The average scientist now produces fewer breakthrough ideas per dollar than their 1960s counterpart.

What went wrong? As economist Gary Becker once noted, parents face a quality-versus-quantity trade-off: the more children they have, the less they can invest in each child. The same might be said for innovation.

Large-scale studies of inventive output confirm the result: researchers juggling more projects are less likely to deliver breakthrough innovations. Over recent decades, scientific papers and patents have become increasingly incremental. History’s greats understood why. Isaac Newton kept a single problem “constantly before me . . . till the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light”. Steve Jobs concurred: “Innovation is saying no to a thousand things.”

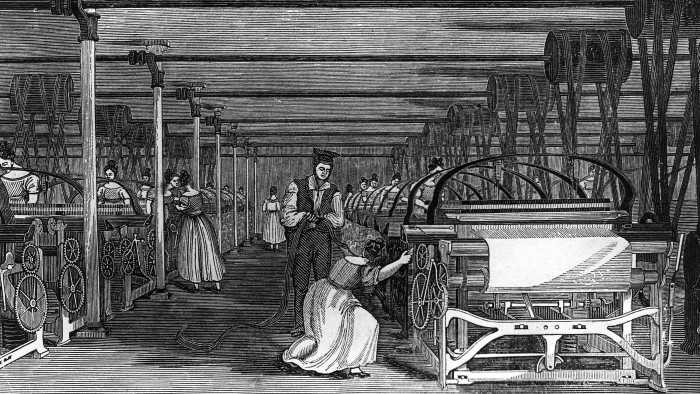

Human ingenuity thrives where precedent is thin. Had the 19th century focused solely on better looms and ploughs, we would enjoy cheap cloth and abundant grain — but there would be no antibiotics, jet engines or rockets. Economic miracles stem from discovery, not repeating tasks at greater speed.

Large language models gravitate towards the statistical consensus. A model trained before Galileo would have parroted a geocentric universe; fed 19th-century texts it would have proved human flight impossible before the Wright brothers succeeded. A recent Nature review found that while LLMs lightened routine scientific chores, the decisive leaps of insight still belonged to humans. Even Demis Hassabis, whose team at Google DeepMind produced AlphaFold — a model that can predict the shape of a protein and is arguably AI’s most celebrated scientific feat so far — admits that achieving genuine artificial general intelligence systems that can match or surpass humans across the full spectrum of cognitive tasks may require “several more innovations”.

In the interim, AI primarily boosts efficiency rather than creativity. A survey of over 7,000 knowledge workers found heavy users of generative AI reduced weekly email tasks by 3.6 hours (31 per cent), while collaborative work remained unchanged. But once everyone delegates email responses to ChatGPT, inbox volume may expand, nullifying initial efficiency gains. America’s brief productivity resurgence of the 1990s teaches us that gains from new tools, be they spreadsheets or AI agents, fade unless accompanied by breakthrough innovations.

AI could still ignite a productivity renaissance — but only if we use it to dig deeper for new and previously inconceivable endeavours rather than merely drilling more holes. That means rewarding originality over volume, backing riskier bets and restoring autonomy. The algorithms may soon be ready; our institutions must now adapt.