Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

“France cannot be France without grandeur,” wrote Charles de Gaulle, but the country somehow managed without for decades. As it leaked power, only the decor remained grand. Many French officials (including the president) work from former palaces or great mansions. The military fly-pasts on Bastille Day are worthy of a superpower. Paris always nurtured a fantasy of the Americans going home one day, whereupon the grande nation would come out of retirement.

Terrifyingly, Donald Trump is making that fantasy come true. France now aspires to lead what you might call “the little west”. Can it? I’ve drawn on recent conversations and briefings with French officials, some of which happened in 18th-century rooms with exquisitely carved ceilings.

The French are congratulating themselves on having been right all along on “strategic autonomy”, their doctrine that Europe shouldn’t rely on the US for its security. Yet they have also had to do some panicked rethinking, because they were wrong on something equally big: friendship with Vladimir Putin.

Treating Moscow as a counterweight to Washington goes back to De Gaulle. Although not keen on the USSR (“the cooking is unimaginative”), he courted the Kremlin. So did Emmanuel Macron, with the approval of pro-Putinist French conservative army officers. Days before Putin invaded Ukraine in 2022, French intelligence was still saying he wouldn’t. The day he did, Volodymyr Zelenskyy rang Macron and asked him to tell his chum, “Stop.”

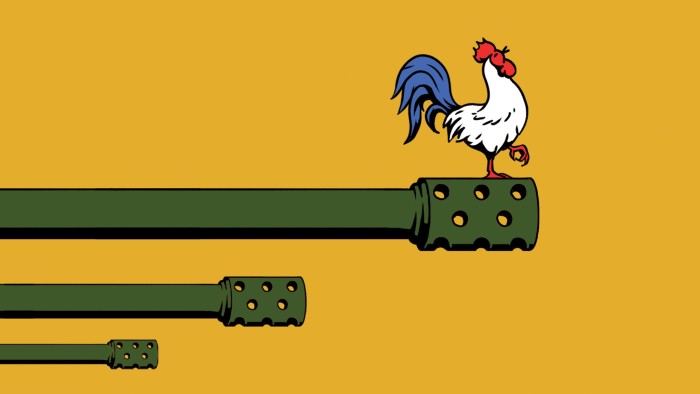

Now France hopes to marshal the anti-Putin west. It can’t do this through military power. “With France there’s always a gap between ambition and means,” says Guillaume Lagane of Sciences Po university. France is only the world’s ninth biggest military spender. It devotes 2.1 per cent of GDP to defence, or 1.6 per cent excluding military pensions. True, it’s proud of having the one European army with recent fighting experience, but that was mostly in the Sahel. It was forced out of there in 2023, just as it has failed in most wars since 1940.

France has an armée complète, supposedly equipped for all types of warfare, but in miniature. For instance, it could currently muster perhaps 5,000 fighting troops against Russia — not enough to impress Putin. Its navy, financed partly to subsidise the country’s defence industry, wouldn’t be much use in a European land war. France talks of offering neighbours its “nuclear umbrella”, but it has approximately 300 nuclear warheads compared with Russia’s 5,580. It wants to nearly double defence spending, but it is mired in a budget crisis.

France knows it can’t be the west’s fist. Instead, it aspires to be the brain and mouth. It sees itself as having Europe’s most sophisticated strategic culture. Its president can talk, in English (unlike certain of his predecessors), to almost any foreign leader, from Benjamin Netanyahu to Iran’s mullahs and Xi Jinping. French officials say Macron speaks to Trump every couple of days. They get irritated when France’s sole rival as convener of the little west, the UK, flaunts its conversations with Kyiv. They don’t think there is any place for a “beauty contest”.

But France can lead only if others follow. Eastern Europe’s response to Macron’s newfound bellicosity is, roughly: “You and whose army?” Countries like Poland can’t wait years to see if Europe can muster its own defence. They need defence now, and they hope Trump will keep providing it. Eastern Europeans also recall that France left Nato’s integrated military command from 1966 until 2009, and flirted with Putin even after February 2022.

Fellow Europeans distrust the priorities of a country that until recently was fighting in Africa and calling itself an “Indo-Pacific power”. A French colonel told me France still wasn’t sure whether fighting for Ukraine was in its national interest. French officials worry more about Isis re-emerging in Syria, or the fallout from Gaza in a country with Europe’s largest Muslim and Jewish populations.

France’s next president may care even less about Ukraine. Putin’s erstwhile admirer Marine Le Pen, the far-right leader, could succeed Macron in 2027. In 2022, she ran for president advocating closer Nato-Russian ties and promising to leave Nato’s military command, though her party now says that doesn’t apply in wartime. Only in 2023 did her party repay a loan that looked like it had been arranged by the Kremlin.

You can’t lead the west if you might abandon the west. The US isn’t the only country that can suddenly change views on Putin. After all, France already did that once.

Email Simon at [email protected]

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram