Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the House & Home myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Fake news of a Scottish ban on domestic cats recently circulated online. The reality was milder: an independent commission had floated ideas to protect wildlife that included “cat containment areas”. However, the report highlighted an issue for pet owners. Conservationists are increasingly critical of the damage companion animals do to biodiversity.

This is awkward if you love pets as well as wild animals. Baskerville, a large labradoodle, is my inseparable companion. In the admittedly unlikely event of a UK dog ban, I would have to dress him in a school uniform and tell people he was a particularly hairy and incoherent teenage son.

I also have a close personal friend in Posset, a tortoise-shell cat I feed when her owners are away.

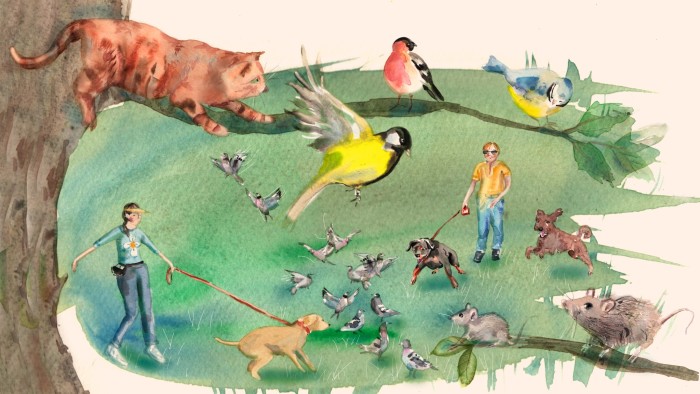

Cats and dogs can be bad for wildlife for two main reasons. First, they sometimes hunt and even kill wild animals. Second, they spread noxious chemicals. I am not talking here about dog pee — though given its impact on lawns, the CIA missed a trick in never using it as a defoliant in proxy wars. The real problem is created by flea and worm treatments.

Predatory behaviour has a higher profile at present. UK nature hotspots sprout notices excluding dogs or telling owners to keep them on the lead.

I have the average Briton’s natural dislike for bossy signage. But in this case, the clipboard-wielding authorities have a point. Pet dogs rarely catch and kill wild animals. What seems like innocent chasing is, however, stressful for the quarry and wastes hard-won energy reserves.

Baskerville is an inveterate scatterer of bird flocks on beaches. These apparently trigger a Terminator-style, heads-up visual display in his brain, complete with cross hairs, closing distances and the flashing message “targets acquired”. A week ago, I innocently took him to Richmond Park, scene of a much-viewed 2011 YouTube video. Here, a Labrador called Fenton pursued a deer herd and was, in turn, pursued by his amusingly exasperated owner.

I kept Baskerville on the lead in the park. I soon found myself in a horizontal position, arm extended like a toppled Lenin statue, after the excited hound had pulled me over. The fault was mine. Baskerville knows he is not allowed to bother horses, cattle or sheep. I have not drummed into him that wild animals are off limits too. I must now do so.

Training is not an option for most cat owners. Cats do not care what people think. Contrary to urban myth, when they bring prey inside they are not saying: “See, Favoured Human! The Mighty Hunter brings you tribute so you may feast!” Ecologists believe cats simply move prey to places they feel safe. A study led by Dr Tara Pirie, now of Surrey University, found that moggies bring home an average of five prey animals a year, a quarter of the total estimated toll. Multiply the latter by 8mn, the UK’s free-ranging cat population, and you get to annual predation of some 160mn creatures.

The majority are rodents. Songbirds account for the bulk of the balance.

I understand why this irks conservationists. But it is counterproductive to propose restrictive measures, as the Scottish commission did.

It is better to encourage mitigation. Studies show the time-honoured expedient of a collar with a bell reduces cat predation by around a half. Collars with rainbow flounces can also alert songbirds to lurking moggies. They meanwhile satisfy the penchant of some owners with Instagram accounts for dressing pets in daft garments.

Dr Martina Cecchetti of the universities of Exeter and Las Palmas tested these and other methods. She says: “Feeding high meat-content food was really effective — there was a reduction of 44 per cent in birds brought home.”

Owners of free-ranging cats value the independence of their animals. But there is something to be said for keeping Fluffy in the house during songbirds’ main breeding season in April and May. About one-third of UK cats already live exclusively indoors.

Fortunately, as cats and dogs age, their predatory urge weakens and they become safer outside. An elderly retriever is no more inclined to chase ducks than its human counterpart is to enjoy drill music.

Pets of any age pick up fleas and worms. But blanket medication damages wildlife. Researchers at the University of Sussex recently found high concentrations of poisons in songbird nests, alongside dead chicks and addled eggs. Parent birds had introduced the toxins in wisps of pet fur taken as nesting material. The same chemicals are leaking into streams and rivers.

More research is needed. Meanwhile, there is a good precautionary argument for treating pets with oral flea medicines rather than the topical kind. Medicines for internal parasites are a whole different can of worms, metaphorically and literally.

Some deep greens believe keeping dogs and cats is entirely unethical, citing such harms as carbon emissions and factory farming for food production. This is unrealistic and reductive. It ignores the benefits pet ownership brings. Companion animals and wildlife both reconnect humans to a wider commonwealth of living things. It is up to us, as the apex species, to reconcile their differing needs better.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram