Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Retail & Consumer industry myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Embarrassment is a powerful emotion in dogs as it is in humans. Baskerville, our family pet, returned from the vet on Monday last week wearing a “cone of shame” — a plastic collar that stops an animal from licking a wound.

His expression was that of a dashing cavalry officer busted down to the ranks for falling off his horse drunk during The Trooping of the Colour. His big, brown eyes asked: “Why has my previously perfect life suddenly gone so horribly wrong?”

Our local veterinary practice, part of a large chain, provided fast, professional and caring treatment for Baskerville’s infected toe. It then stuck us with a bill for just under £250.

This seemed a lot, albeit that we also splashed out on three high-end worming pills. Fellow pet owners whimper of treatments costing many thousands.

It was during my subsequent research into the soaring cost of keeping a dog or cat that I found evidence of human embarrassment suffered by those who run large vet practices as acute as that of our labradoodle.

This came in the form of scissor icons in a critical report on the business practices of vet chains that cater for pets published by the Competition and Markets Authority in February. I understand the scissors represent redactions demanded by lawyers representing the chains.

They appear where, contextually, you might expect the CMA to remark: “Those vet chains! They’re making out like bandits!” There are 843 scissor icons in the 124-page report and you can bet the lawyers asked for far more. The report “betrays signs of a struggle”, as a police forensics officer might put it.

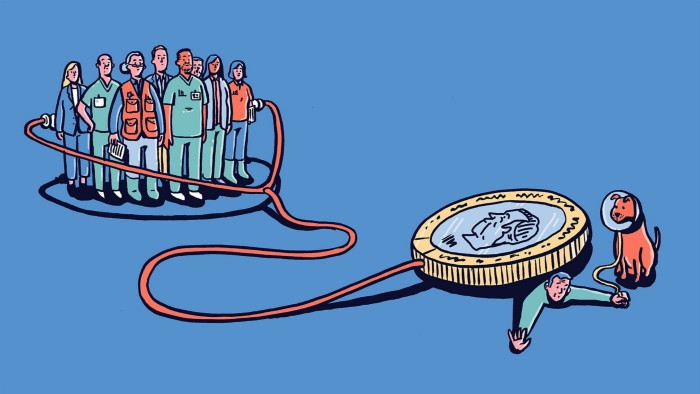

Three key CMA findings survived the tussle. First, the cost of taking a pet to the vet rose by 60-70 per cent in 2016-2023, when consumer services price inflation was 35 per cent. Second, this is not satisfactorily explained by fancier treatments becoming available. Third, some 60 per cent of neighbourhood vets are now controlled by large chains, compared with 10 per cent in 2013.

Three out of six of the large chains — IVC, VetPartners and Medivet — are owned by private equity. The other three are corporates.

By some weird coincidence, these entrants have all wound up putting money into a highly fragmented industry, previously dominated by owner-practitioners whose motivations had not been primarily financial and whose customers will often put up with price rises. What possible game plan could they have?

A realist might reply: “Consolidation, systematisation, reaping economies of scale, cutting costs and raising prices.”

Turning to Baskerville’s recent vet bill I discerned a classic razor/blades pricing strategy, where profitability depends on discounting the customer’s primary purchase and marking up sales that result from it. The consultation was a reasonable 70 quid or so. The bulk of charges was accounted for by drugs. These were supplied at up to eight times prices advertised by online pharmacies.

Then I looked at published accounts. All those redactions had made me curious about the finances of the vet chains. High profitability is sometimes a sign that competition in a market is weak.

The veterinary division of London-listed Pets at Home has a profit margin fatter than an elderly golden retriever that ate the Sunday joint while its owner was out of the kitchen. It stood at 43 per cent at the last record date. But this apparently reflects hefty cross subsidies from pet supply stores where many Pets at Home practices are located.

IVC, VetPartners and Aim-listed CVS reported profit margins of around 20 per cent at their last record dates, as measured by adjusted ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation). That figure may be more representative of large vet chains. It is not excessive for service businesses.

IVC is the biggest chain and stands out for the aggressive pace of its expansion. It has more than 900 vet practices, around 24 per cent of the UK total, according to CMA data. Owners aim to create a valuable asset they can sell for a capital gain. At the end of last September, net debts stood at around £4bn, a racy six times adjusted ebitda.

So what is a dog or cat owner to do in the face of rising bills? Here are some suggestions:

-

Ask local vet practices what prices they charge for standard treatments such as vaccinations, spaying, castration and filling in travel permits.

-

Find out who owns the business. Remaining independents may have more discretion to discount charges.

-

Register with a vet whose charges appear sensible and whose services are recommended by other pet owners.

-

Be wary of signing up for subscription services that seem affordable on a monthly basis, but look expensive when you multiply by 12.

Help may be at hand. The CMA is due to publish an action plan for making vet services more competitive in September, finalising it next February.

Spare a thought, meanwhile, for hard-working vets. Some are now saddled with sales targets and monthly reviews of their financial performance. Vet chains should remember the historic lessons of the AA and Royal Mail — alienating a publicly popular workforce can be bad for business.

As for Baskerville, his toe has healed nicely. He is spared the plastic collar and people no longer laugh and point as he walks down the street. But we will keep the cone of shame to remind him that owners call the shots for pets at home — if not at the checkout of the local vet.

Jonathan Guthrie is a writer, an adviser and a former head of Lex; [email protected]