Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

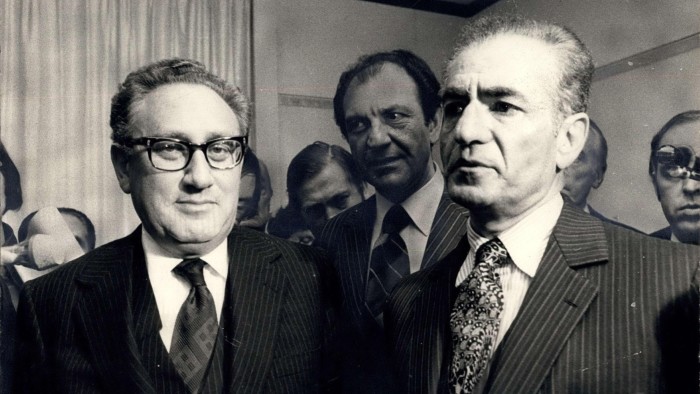

The writer is director of the Iranian History Initiative at LSE and author of ‘Nixon, Kissinger and the Shah: the United States and Iran in the Cold War’

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s unilateral military strike on Iran is predicated on the idea that either the Islamic Republic can be forced to give up its nuclear programme, or it can be replaced with a regime that will comply with the demands of Israel and the US to abandon its nuclear aspirations.

The reality is that no Iranian regime — past, present or future — will surrender Iran’s nuclear ambitions. If anything, by attacking Iran’s nuclear sites while Iran was negotiating with the US, Israel has reinforced the incentive for the Islamic republic to rush to acquire a nuclear deterrent.

Iran’s nuclear dreams, and the west’s nuclear nightmares, were not born with the Islamic republic in 1979. It was the shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who dramatically accelerated the country’s civilian nuclear programme in 1974 after the global energy crisis sent oil prices soaring. Then, as now, there was deep concern in Washington that a nuclear Iran would set off a cascade of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, endangering Israel.

When the shah turned to the US to supply Iran with nuclear reactors, secretary of state Henry Kissinger tried to maintain US “veto rights” over Iran’s spent nuclear fuel. His fear was that Iran, like India or Pakistan, would use its civilian programme to stockpile fissile material that could eventually be used for a bomb. Today, Iran has mastered the nuclear fuel cycle and is, by most estimates, weeks away from having enough enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon.

The shah balked at the idea that Iran should be treated any differently to other signatories to the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Not even Kissinger, the master diplomat, could convince the shah to agree to additional constraints and safeguards on Iran’s nuclear programme. The shah insisted on Iran’s right to enrich and reprocess its own nuclear fuel, rather than relying on any foreign country to fuel its reactors. The Islamic republic agreed to these additional constraints and safeguards in the 2015 nuclear deal that Trump tore up in 2018.

“Bullying rarely succeeds and has never succeeded against the nation of Iran,” warned former Iranian foreign minister Ardeshir Zahedi in 2018. From his exile in Switzerland, the shah’s former son-in-law took out a full-page ad in The New York Times attacking comments by then US secretary of state Mike Pompeo that Iran would be crushed if it didn’t comply with Washington’s demands. “Are the brains at the state department and the CIA this ignorant of history?” asked the man who had signed the NPT on Iran’s behalf in 1968.

Zahedi remembered that despite the shah’s close relationship with both the US and Israel, there was a deep discomfort in the west with the idea of a nuclear Iran. Paul Erdman’s 1976 novel, Crash of ’79, captured the mood. The bestseller envisaged a scenario where a megalomaniacal shah secretly builds a nuclear weapon and goes to war to dominate the Middle East.

The notion of a powerful Iran, regardless of who rules it, is the stuff of nightmares in Washington and Israel. It seems unlikely that Israel, itself an undeclared nuclear weapons state, will ever accept the idea of a nuclear Iran, even one that isn’t led by theocratic clerics. An Iran with nuclear weapons would end Israel’s nuclear monopoly in the Middle East and change the strategic balance in the region forever.

The Israelis know full well that no Iranian regime is going to accept a diminished role in the Middle East. Iran, after all, is a country of 90mn people, three times the size of France, and sits on the world’s second-largest natural gas reserves and third-largest crude oil reserves.

Any Iranian leader must contend with the reality that US policy towards Iran must take Israel’s interests into consideration. The shah himself knew this. He openly complained of the pro-Israel bias of the American press and believed in the power of the Israel lobby in the US. These same concerns are shared today by at least a segment of the Maga movement, who resent the idea of Israel dragging the US into a war with Iran.

Future Iranian leaders, like past ones, will be acutely aware that a strong and powerful Iran will never be welcomed in Israel or Washington. Unless Iran is willing to accept a diminished status in the region, which no Iranian politician can accept in an era of populist nationalism, then the logic of Iran seeking a nuclear deterrent seems inescapable.