Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

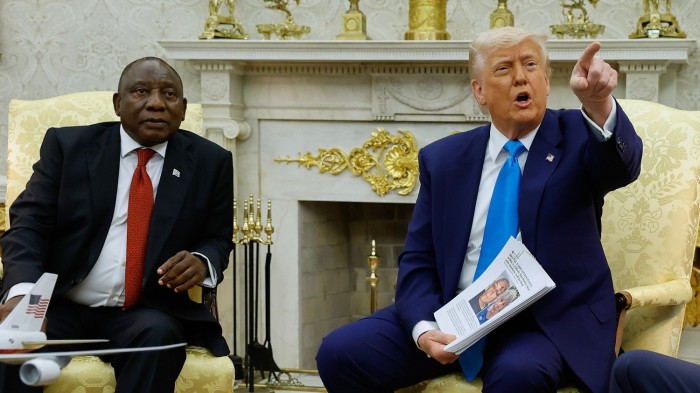

There is no white genocide in South Africa, but there has certainly been a mugging in the Oval Office. When Donald Trump forced his guest, South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa, to watch excruciating footage of hate speech and fake evidence of burial grounds of white farmers, he proved that no visitor to the White House is safe from the sort of ritualised humiliation infamously meted out to Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Leaders of other nations will have to think hard about whether it is worth seeking a once-coveted meeting in the Oval Office if the chances are that they are being set up for an ambush.

Trump’s parade of falsehoods was clearly directed at his Maga base. No one who knows South Africa could take seriously his portrayal of the country. It is a fact that violence is commonplace and that Afrikaner farmers are sometimes the victims. But to say this amounts to a genocide is a lie, one that wilfully ignores the fact that the South Africans who suffer disproportionately from violence are non-white.

For the neutral observer — and potential tourist or investor — South Africa’s reputation was ritually trashed in prime time. The entire optics of the event, in which Trump deferred to white golfers over a Black president and cabinet ministers, evoked nasty echoes of apartheid.

Given the probability of an ambush, Ramaphosa must have debated the wisdom of showing up at all. The hour of ignominy was evidently the price extracted for starting a dialogue after months in which Pretoria’s representatives in Washington have been stonewalled and its ambassador expelled.

On balance, Ramaphosa and his carefully selected delegation of prominent Afrikaners, including a cabinet member, a multi-billionaire and two celebrity golfers, acquitted themselves as well as could be expected. The wily Ramaphosa did not rise to Trump’s bait.

The South African delegation privately assessed, rightly or wrongly, that it left Washington in a marginally better position than it arrived. Talks have started aimed at mitigating the 30 per cent tariffs announced on “liberation day” and at fostering US investments in critical minerals and telecoms, including by Elon Musk’s Starlink.

The White House showdown raises broader questions. One is how countries should navigate a world in which the US has adopted its own form of confrontational “wolf warrior” diplomacy. It was a minor victory for Ramaphosa that Trump did not raise Pretoria’s suit against Israel at the International Court of Justice, nor rehearse criticism about its cosy relations with Russia, China and Iran. Pretoria should stick to its nonaligned status, though that does not mean pandering to dictators. Showing up in Washington was part of a high-risk gamble to prove it values relations with the US and the west more generally.

It is at home that Ramaphosa needs to act most decisively. He rightly condemned radical opposition leader Julius Malema’s racial hatred and championing of mass expropriation. That way lies Zimbabwe. The one-year-old government of national unity, of which the pro-business Democratic Alliance is a part, is the ANC’s best chance in years to drop stupid rhetoric and bad policies.

It must take violent crime more seriously. That means beefing up law enforcement. But it also means tackling the causes of crime — unemployment and poverty. The ANC needs to drop its ingrained antagonism to the private sector, which holds the key to many of the country’s structural problems. Its policies must go beyond enriching a coterie of cronies at the expense of broader economic dynamism. Radical change is in order — not because Trump put on a grotesque show, but because South Africans demand it.