Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the House & Home myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Some subjects of conversation are perennial in English pubs: football, the weather and the likely outcome of unlikely boxing matches (eminent actor Dame Judi Dench versus veteran broadcaster Sir David Attenborough, for example). When all such avenues have been explored, not to say ransacked and reduced to rubble, one tipsy regular will turn to another and remark: “Did you know that a swan can break a man’s arm with a blow of its wing?”

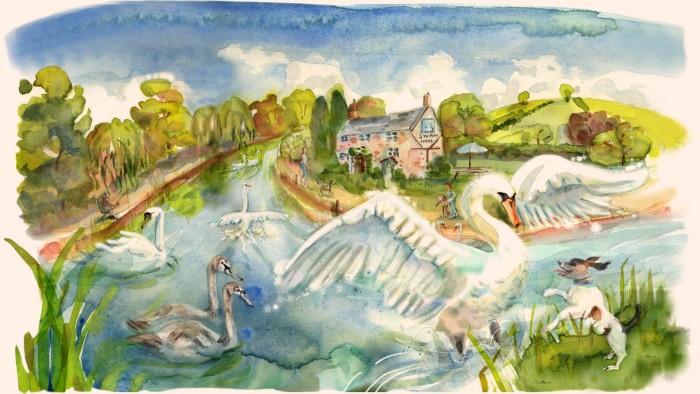

The topic of swans is a lot less random than an outsider might imagine. Mute swans, with their orange beaks and elegantly curved necks, loom large in the English psyche. If the pub is close to water, it is liable to be called The Swan. It may even be located on one of the country’s many Swan Lanes. If the tavern is near the Thames, thirsty swan counters may drop in annually for a pint.

American readers who live by lakes sometimes regale me with accounts of ospreys snatching up fish in their talons. UK readers who reside by the water or ramble around it will more commonly encounter swans. So here, therefore, is my research into the secrets of harmonious cohabitation.

Swans are territorial in the breeding season, which is another way of saying they protect their families. I was reminded of this on a visit to the village of Abbotsbury in Dorset, the site of the only remaining managed swannery in the world. As I walked by, a magnificent male reared to his full 5ft in height, stretched out his 7ft wingspan and hissed like a steam iron. My arms were still miraculously intact when I met up with Steve Groves, swanherd. His advice to anyone encountering an anxious swan is: “Keep eye contact and back up. Do not turn away. This is when it might go for you.” Especially if you have a four-legged friend with you; swans react particularly badly to dogs, which regularly displace or kill nesting birds.

Groves knows what he is talking about. Abbotsbury is key to understanding the special relationship between swans and humans in England and he has worked there for decades; for the past eight years as swanherd — a title that likely dates back to the 15th century. In the Middle Ages, swans were semi-domesticated as trophy poultry for the banquets of monarchs and aristocrats. Monks — including those of the Benedictine monastery at Abbotsbury — swerved prohibitions against eating meat by claiming swans were distinctly fishy. Bigwigs with rights to local swans marked their bills with their insignia and paid swanherds to nurture the birds. The crown could claim unmarked animals, and still can.

Swan privatisation persists in just two places, however. First, Abbotsbury, whose proprietor, the Ilchester Estate, runs it as a conservation centre, visitor attraction and home to more than 600 birds. Second, the Thames, whose swans belong either to the monarch or the Dyers and the Vintners, two City of London livery companies descended from medieval guilds. Swan is no longer on the menu in either location. But English swans retain their willingness to live at close quarters with humans.

We should repay the compliment. Like most of us, swans just need space. Keep dogs on leads near them. Grain or even porridge oats are a better supplementary feed than bread, adds David Barber. He knows his swans, too. His title of King’s Swan Marker puts him in charge of “swan upping”, the annual count of birds on the Thames.

Avian flu hit swans badly, Barber says. His stretch of the river produced just 86 cygnets last year. He hopes numbers will be back over 100 this year. That depends partly on fewer thugs shooting swans with air guns and catapults (incidents of which are regularly reported to Thames Valley rehabilitation centre Swan Support) and on the public, police and courts discouraging these illegal acts.

Anglers, for their part, should destroy discarded line safely. It can easily entangle beaks and webbed feet.

Better water quality is needed too. Sewage dumping by utilities such as Thames Water and fertiliser run-off from farms have left English watercourses badly polluted, harming the aquatic plants swans eat.

“I love these regal birds,” Barber says. “They always look so serene.” I fear that for some of my other compatriots, familiarity has instead bred contempt. If you are a twitcher seeking out the latest nondescript vagrant, it takes an effort to remember that the swan sailing on your local park’s lake is a stunningly beautiful bird. You should ignore the regulars at The Swan Inn, meanwhile. It would be disrespectful to theorise about pugilism involving national treasures Dame Judi and Sir David. And a swan cannot break a man’s arm.

“The wrist bone has a solid lump on it that can be used as a weapon,” Groves reports. Swans thump him regularly when he lifts them off their nests to count eggs and cygnets. But he has only ever sustained bruises.

I’m informed by AI, which we are all supposed to deploy these days, that a force of 3,000 newtons is normally needed to fracture a man’s arm. In flight, the downstroke of male swan’s wing might generate only around 300 newtons. If you have different numbers, please share them. At a later date, we will tackle a second crucial question: whether torrential rain is really, as the English are wont to call it, “nice weather for ducks”.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram