Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

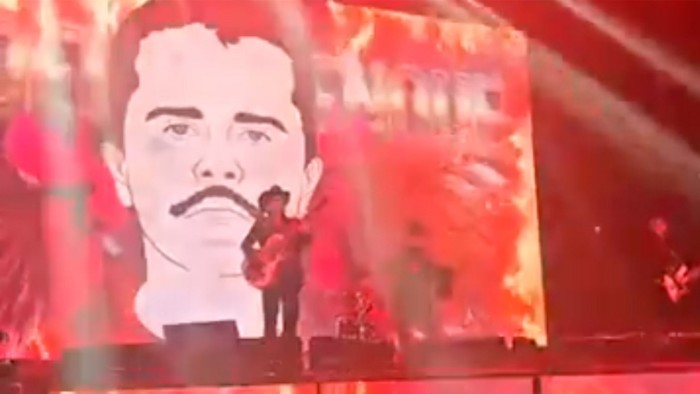

Thousands of sweaty fans packed into a concert hall in Guadalajara last month to hear Los Alegres del Barranco perform their hits — including jaunty ballads, like “El Del Palenque”, that celebrate the exploits of drug traffickers. When images of that song’s hero, cartel leader Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera, appeared on the screen, many revellers erupted into cheers.

Such scenes are typical of narcocorridos, a popular genre of Mexican regional music that romanticises cartel figures, their armies and their journey from poverty to riches. But the country’s reaction to this particular concert was different. The event took place weeks after the discovery of a cartel training camp run by Mencho’s men, full of piles of clothing and bone fragments. Footage of the concert ignited political outrage across Mexico.

The fallout has been swift. Band members had their US visas cancelled for allegedly supporting Oseguera’s murderous Jalisco New Generation Cartel, listed as a terrorist organisation by the US. Several local governments in Mexico have passed or proposed bans on public performances of narcocorridos. Other popular bands have sworn never to play trafficker-inspired songs again.

Mexican regional music has exploded in popularity in recent years thanks to streaming and social media — a phenomenon that made Mexican singer Peso Pluma the most streamed artist on YouTube in the US in 2023.

But political opposition to narcocorridos is growing. The Guadalajara concert came at a particularly sensitive time for Mexico. Combined, homicides and disappearances reached around 40,000 people last year, close to a record high, with sporadic decapitations and massacres across different states — polls show security is the country’s number one concern.

Following the discovery of Oseguera’s killing ground, President Claudia Sheinbaum was forced to respond with a new plan to locate the country’s 120,000 missing people.

Sheinbaum is also battling to convince US President Donald Trump that she is doing enough to dismantle organised crime. He has said that Mexico’s government has an “intolerable alliance” with drug cartels who supply the fentanyl that kills tens of thousands of Americans each year.

With roots in Spanish medieval epic poems, ballads — or corridos — about local bandits became popular during the Mexican revolution in the early 20th century. The shift to drug dealers happened in the 1970s and 1980s, says Rafael Acosta Morales, associate professor of Latin American cultural studies at the University of North Carolina.

“At that point, the corridos were absolutely fictional, and mostly they were just things that some composers thought would sound cool,” he says. “Not very long after, we started hearing corridos about particular drug runners.”

Corridos became a key element of propaganda for cartels, he adds. On the streets of cities like Culiacán, Sinaloa, home to the Sinaloa Cartel, bands play open auditions of corridos, hoping to be hired for local parties.

Sheinbaum has said that musical groups shouldn’t be apologists for violence, but she is against banning songs. Instead, she is promoting a government-sponsored music contest with “positive” messages.

The industry’s defenders say their music reflects reality, and that performance bans will not loosen the grip cartels hold over Mexico. Juan Carlos Ramírez-Pimienta, Spanish professor at San Diego State University, also points out that much popular culture is controversial, including hyper-violent gangster films.

Previous attempts to ban narcocorridos have failed. “They’ve been going on since the ’90s,” Ramírez-Pimienta says. “I don’t think popular culture can be legislated.”

Los Alegres del Barranco were called in by Jalisco state prosecutors last week. But their song about Oseguera went viral. The question is whether a crackdown will reshape the industry or drive it underground. Acosta Morales believes the latter. “If you censor narcocorridos, you’re just turning narcocorridistas into popular heroes.”