Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

The writer is a professor at Harvard University and former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers

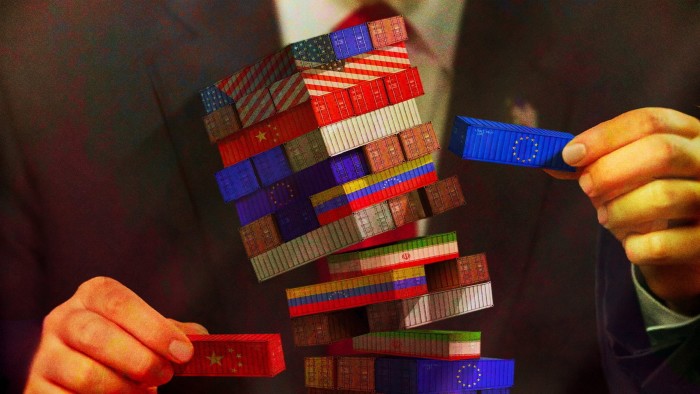

A hopeful endgame for the tariff fiasco is making the rounds on Wall Street and in Washington. Donald Trump cuts quick deals with countries around the world, declares victory, and eliminates or dramatically reduces the “reciprocal” tariffs, leaving only the 10 per cent across-the-board ones plus miscellaneous others like steel and aluminium. The hope is that markets would cheer the certainty, businesses would return to planning for their futures, and everyone could turn their attention elsewhere. That this settlement would be viewed as a victory shows just how far and how quickly the Overton window — or policy ideas regarded as acceptable — has shifted to a tariff rate that would put the US on par with Iran and Venezuela.

Consider that all of this started with an average tariff rate of 2.5 per cent in 2024, a rate that itself was elevated by the tariffs that Trump imposed in his first term and that Biden then added to. Most analysts — myself included — thought that market pressure would force Trump to scale back once he returned. Investment banks were bandying around scenarios like a 5 percentage point increase in the average tariff rate.

We are now at a 24 per cent average tariff rate, making the US the highest tariff country in the world — leapfrogging pikers such as Iran and Venezuela with average rates of 12 and 14 per cent respectively. In fact, there is no country with a population above 1mn and a per capita income even a quarter as high as the US that has an average tariff rate above 10 per cent.

Moreover, it is possible this could go even higher if full tariffs on Canada and Mexico and the promised tariffs on pharmaceuticals, semiconductors and other sectors happen, or if the US escalates further in response to foreign retaliation.

More likely, however, is that Trump has been so burned by the hot stove that he’ll pull his hand away. In the past, he has been able to make a big deal out of small concessions, and he may well end up doing that here.

How exactly you negotiate deals with the 60 different economies currently facing “reciprocal” tariffs on top of the 10 per cent across-the-board tariff is hard to imagine, but let’s suppose that he pulls it off. While anything is possible, the most likely landing place is that he will retain the across-the-board tariff which he campaigned on and considers central to shifting the US revenue base, while maintaining a higher tariff on certain countries like China and certain products such as steel. The result would be that the US would have a 12 to 15 per cent average tariff rate. That is much lower than now — but still very high, with inevitably bad consequences.

It is possible the market would breathe a sigh of relief that rates settled lower than they might have been otherwise, but that level would still result in a substantial reduction in the volume of imports and exports. Americans would face higher prices, lower quality and a shift to worse jobs in import substitution industries from the higher productivity export and service jobs they are in now.

Moreover, even tariffs at this level would guarantee extremely high trade policy uncertainty for at least the next four years. When businesses are not sure what future policy will be, it can pay to wait until this is resolved before making big, irreversible investment decisions. The result is less investment and lower growth.

Uncertainty does not work in the way often supposed, namely the chance that something bad will happen. Instead, it reflects variance in future outcomes — which could be tariff reductions or tariff increases. In the past 50 years, the average tariff rate has never changed by more than 1 percentage point in a single year. In most years, they have not changed by more than a tenth or two (although other trade restrictions that have changed over time, like quotas, are not captured by this measure). If the US were starting from an average tariff rate of say 12 per cent, even with a less erratic and more predictable president, businesses would have to scenario plan around a much wider range of tariff possibilities than they have faced in a very long time.

Unfortunately, there is no real way out. Even if Trump backs down from his most extreme proposal he will have succeeded in shifting the debate on tariffs and in building uncertainty, which itself can act like a tariff. It will be hard to put the evil genie back in its bottle. The best option would be for Congress to take back the power to set tariffs — which would at least be more predictable than leaving them to the whims of one person.