Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Johnny Echols, lead guitarist for the 1960s rock band Love, is a fount of stories. In a podcast interview with superstar producer Rick Rubin a few years ago, he talked about happy accidents in the recording studio, rivalries within the band, meeting The Beatles when they were still The Quarrymen and his friendship with The Doors. But there’s one story in particular that resonates.

Echols used to hang out with Little Richard and his band, including an unremarkable journeyman guitarist called Jimmy James, whom Little Richard seemed to value more as a driver and a roadie than as a musician. The guitarists in all the top bands of the day were given an invention called the Vox Wah Wah pedal. Vox was hoping for some promotional value, and its pitch was that the pedal could make your guitar sound like a trombone.

“If I wanted to do that I would play a trombone,” recalled Echols. “So I put the damn thing in the closet and never never bothered with it.”

A year or so later, Echols gets a call from a friend urging him to drive across California to see this amazing new guitarist who’s come over from England: Jimi Hendrix. Excited, Echols makes the trip — and is astonished to realise that he’s seen Hendrix before: it’s Jimmy James, the driver and fill-in guitarist for Little Richard. Now he’s playing through the Wah Wah pedal — and he sounds incredible.

Without the Wah Wah pedal, Echols reflected, “there would have been no Jimi Hendrix. Jimi was the effects. That’s what made him sound different, that’s what made everybody look, because he didn’t sound like every other guitar player.”

Echols isn’t denying that Hendrix had sharpened his skills and matured into a superb musician. “I still wonder how in the space of a little over a year he goes from being just a so-so guitar player to being God . . . I always said, ‘Man, you must have taken a trip to the crossroads.’”

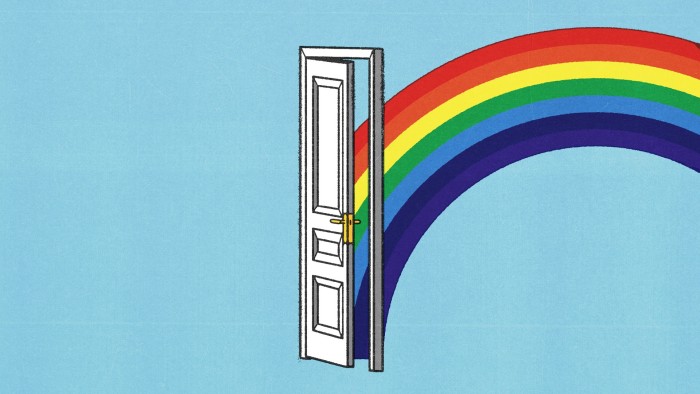

Still, it is hard to hear the story without thinking of the way new technologies arrive in our lives, to be embraced by some people and ignored by others. In Lynn White Jr’s famous history, Medieval Technology and Social Change, he opined that a new technology “merely opens a door, it does not compel one to enter”.

True. But once the door is open, someone is likely to be curious about what lies on the other side: your boss; your colleague; a rival company; a rival nation; a roadie who sometimes plays guitar. With this in mind, another historian of technology, Melvin Kranzberg, coined Kranzberg’s First Law: technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.

Kranzberg’s point was that technology changes the world in unexpected ways “that go far beyond the immediate purposes of the technical devices”.

The bar code is a useful example. It seems a simple enough idea, designed to speed up the process of identifying objects or types of objects. An early version from the 1950s involved machine-readable thin and thick lines on the side of railway cars. Yet the key point in the development of the bar code was not the initial eureka moment (Philadelphia graduate student Joseph Woodland combed his fingers through sand on the beach in 1948, and realised thin and thick lines could encode information) nor the practical implementation, when IBM’s George Laurer developed the familiar rectangular bar code and used lasers to scan it in the early 1970s.

Instead, it was a meeting between members of two administrative committees, one representing US retailers and the other representing food manufacturers. The meeting was tense because, of course, different interest groups had different hopes for the technology, and nothing could happen until the retailers agreed to install scanners and the manufacturers agreed to print bar codes. It took a lot of haggling but eventually they reached a compromise.

Then the playing field started to tilt. The bar code solved the kind of problem that family-run corner stores didn’t really have, such as long checkout queues, staff stealing from the till, or stocktaking. The little striped label was transformative for big-box retailers and is credited by the economist Emek Basker with helping Walmart achieve a decisive cost advantage — and catalysing the economic integration of the US and China. The simplest-seeming idea — a way to speed up checkout and stocktaking — created winners and losers on a grand scale.

What of today’s digital box of tricks, generative AI? Many journalists have received its arrival with the same enthusiasm that Echols received the Wah Wah pedal. He didn’t want to sound like a trombone; we didn’t want software that couldn’t talk to sources, wrote in clichés and sometimes made stuff up. Figuring out what to do with it required more than simply being open-minded, although open-mindedness is a start.

An old friend of mine, author and game designer Dave Morris, realised early that there was little point in asking ChatGPT to write for him. Instead, he has used NotebookLM to answer questions about his own creations (did I ever name the mountain range to the south-east of an imagined kingdom?); Claude to produce examples of “moral riddles” from late medieval literature, and to straighten out a garbled scan of an old typewritten manuscript; ChatGPT to brainstorm ideas; and Perplexity for fact-checking. It’s an impressive range of applications, and as a rebuke to those of us who think we’re too old to learn new tricks, Morris has been writing professionally for more than four decades.

I’m still struggling to make these tools work for me, but I realise I can’t afford to leave them in the closet. As Echols reflected about Jimi Hendrix, “he knew how to use [the technology] and he made it his own. He was so identified with that. He also had the foresight and the musicianship to use it properly, because I saw the same damn thing, and I didn’t do it.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram