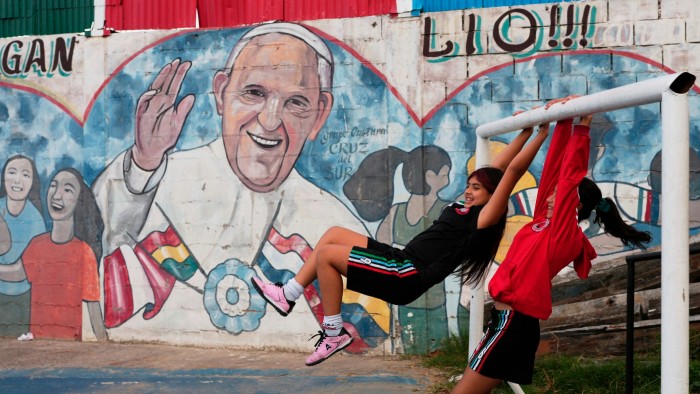

For many, Francis was the “people’s pope” or the “pope of the poor” but in his native Argentina, the pontiff had another name: the Peronist pope.

Depending on your political persuasion, that would either be a badge of honour or a mark of shame. Peronism has defined and divided Argentina for much of the past century, and few Argentines are indifferent to the populist nationalist movement inspired by General Juan Domingo Perón in the 1940s. Francis was swept up in that controversy.

The late pontiff shared key social priorities with the movement, and some Peronist leaders were big fans, including former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

“Perón used to say that the doctrine of Peronism was the social doctrine of the church,” said Ignácio Zuleta, author of a study of Francis entitled The Peronist Pope. Both church and Peronists emphasised social justice and the fight against poverty, while advocating conservative social mores.

Peron’s first government legalised religious education and the young Jorge Mario Bergoglio “grew up in the Argentine church with this formal respect and institutional gratitude towards Peronism”, said Zuleta.

At a time when the Vatican had turned decisively against liberation theology — the radical blend of religion and revolution that swept through Latin America in the 1970s — Peronism also offered the young Francis a way to pursue social justice without being accused of Marxism or insurrection.

But that also brought him into conflict with Argentina’s conservatives and liberals, who accuse the Peronist movement of ruining the once-wealthy nation’s economy, presiding over rampant corruption and creating a large clientele of dependants living off the state.

“In Argentina, he was seen more as a Peronist than a pope,” said Marta Lagos, a Chile-based pollster who runs Latinobarómetro, a comprehensive survey of regional opinion.

Francis himself was always careful in public to deny a link to Peronism. “I have never been a member of the Peronist party, I have not even been a militant or sympathiser of Peronism,” he once said, before adding provocatively: “And supposing one was to have a Peronist concept of politics, what would be bad about that?”

In private, he was apparently more candid. Eduardo Valdés, a Peronist legislator and former Argentine ambassador to the Vatican, recalled Francis greeting Brazil’s visiting president Dilma Rousseff in 2014 with the proud words: “I am the first pope who is a supporter of the San Lorenzo football club, the first Jesuit pope and the first Peronist pope.”

Valdés said the remarks were intended as a joke, though his own handle on X describes him as “former ambassador to the Peronist Holy See”.

After the news of Francis’s death, there was a Peronist outpouring of grief. “Our sadness is infinite,” said Kirchner. She had enjoyed several long Vatican lunches with Francis as head of state and accompanied him on trips to Cuba and Paraguay. “All the tribes of Peronism are in mourning,” noted a senior Argentine diplomat.

At the other end of the political scale, the country’s anarcho-capitalist President Javier Milei had attacked Francis during his election campaign as “an imbecile who defends social justice” and a “filthy leftist” — though he later visited him in Rome and claimed after news of the pontiff’s death that their differences were “minor”.

The pope was also notably cool in his first meeting with Argentina’s property tycoon-turned-president Mauricio Macri, a conservative and opponent of the Peronists, in 2016. That encounter lasted just 22 minutes, though a subsequent meeting with the multi-millionaire Macri, his third wife and their children lasted longer.

Outsiders might be surprised to learn that Francis was markedly less popular in his native Argentina than in neighbouring Brazil, or in other Latin American Catholic strongholds such as Mexico or Colombia — a gap that Lagos put down to his strong association with Peronism in Argentines’ minds.

The pope’s critics within the Catholic Church accused him of two traits detractors often associate with Peronism: an intolerance for dissenting points of view and chaotic governance.

But in spite of his Peronist reputation, Francis in fact had a tempestuous relationship with all of Argentina’s recent presidents, even initially with Kirchner, who later warmed to him.

Cristina’s husband, Néstor Kirchner, president from 2003-07, viewed the cleric, then archbishop of Buenos Aires, as the “leader of the opposition”.

The pope’s relations with Macri and his Peronist successor Alberto Fernández were soured by their support for legalising abortion in Argentina.

The numerous political controversies over the “Peronist pope” also explain why this very Argentine pontiff refused ever to return to his beloved homeland once installed in Rome: he feared that a visit would be hijacked by warring political factions for their own ends.

Whether Peronist or not, Francis’s life-long commitment to fighting poverty and social justice made him a natural ally for Latin American leftist leaders such as Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Bolivia’s Evo Morales.

“He was the best friend of the poor and marginalised,” said Peronist social leader Juan Grabois. “He loved them and he reminded us of the obligation which we Christians and all people of goodwill have to look after them, be close to them and to fight for their rights.”