Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

In the seaside town where my parents had a weekend place, having a shiny car was risky. Wild turkeys lived in the marsh. If they wandered into your driveway, one might see its own image in your door panel and pick a fight with it. This left your car with beak marks and could wound the turkey too.

René Girard might have found metaphorical use for this. The French theorist’s great idea was that religion and culture grow out of what he called mimetic rivalry. Human beings, uniquely, choose the objects of their desire largely on the basis of what other people desire. “There is nothing, or next to nothing, in human behaviour that is not learned, and all learning is based on imitation,” he writes. But while mimesis helps us learn, it also leads to escalating competition, and ultimately violence. Religion evolved as a means for containing rivalry by projecting communal violence on to an arbitrarily chosen sacrificial victim, the scapegoat.

I like Girard’s theory because I tried and failed to come up with it myself. Some decades ago, I wrote a notably bad PhD dissertation arguing that the English-speaking enlightenment philosophers were mistaken in thinking that rational action starts with pursuing pleasure and avoiding pain. That’s too individualistic; we learn what to want by watching others. I was a proto-Girardian without having heard of him (Anglo-American philosophy departments discourage the reading of French social scientists). I got my degree, but I was no philosopher and switched to finance.

I first heard of Girard a few years ago on an economics blog. Reading him, I felt a rush of satisfaction that someone had made it down the road on which I got lost. And I think about Girard often now because in the US we live, more and more, in the political world that he described: a stark rivalry in which each side envies, then attempts to appropriate, the other’s sources of value and identity.

This has been going on for a long time. What is the “revolutionary” anti-government conservatism that began in the 1980s, if not a hijacking of the anti-government politics of the 1960s and ’70s? Anti-woke campaigners respond to left-wing censorship by removing “offensive” books from libraries. The left comes after Trump through the institutions of justice; Trump does the same in return. My gentle liberal friends buy guns and canned foods like the rightwing preppers they once mocked. Most tellingly — as Girard observed at the end of his life — the status of victim or scapegoat becomes itself the object of mimetic rivalry. “There is never anything on one side of a rivalry which, sooner or later, will not be found on the other,” Girard writes. Read him and you start seeing this stuff everywhere. Choose your enemies carefully; you will resemble them before very long.

The point is not that the two sides of the American political divide are interchangeable; the distinctions between them are morally important. The point instead is the inevitability of irrational escalation. People caught in mimetic rivalry can only see literal or rhetorical violence as originating with the opposite side. “Violence is always perceived as being a legitimate reprisal,” Girard writes. “No one ever feels responsible for triggering it.”

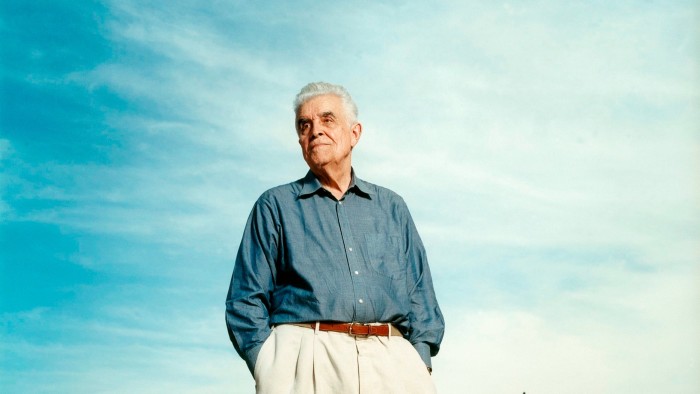

Girard is having a moment. There is a new documentary about his work. In the FT, Orlando Reade has described how the theory has special appeal to intellectuals on the right. Trumpers cast themselves as scapegoats, and see the Christian exceptionalism and occasionally apocalyptic tone of Girard’s theory as justifications for anti-government nihilism. Peter Thiel and JD Vance are both fans.

As always happens when an intellectual becomes popular, distortions have followed. The main problem, though, is not misinterpretation. It’s omission. What is often left out of discussions of Girard is the most challenging part of his theory, about how we break the cycle. Here he turns to one of the firmest messages of the gospels: the injunction to love our enemies. Girard knew, as we all know, that renunciation and mercy are almost impossibly hard, and quite alien to human culture. Yet he argues that it is the moments when the mimetic crisis has reached a hysterical crescendo, when “the vanity and stupidity of violence have never been more obvious”, that it is possible to see our enemies in a new way. Might we not be living in such a moment right now?

Robert Armstrong is the FT’s US financial commentator and writes the Unhedged newsletter

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning