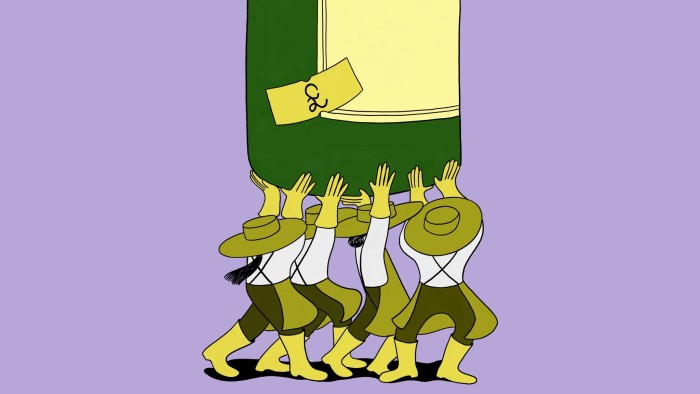

Much is said and written about the growing environmental sustainability and diminishing financial sustainability of wine production, but very little about the third pillar of sustainability, how those responsible for it are treated.

Hence the title of a recent workshop organised in London by the UK’s co-operative buying organisation The Wine Society: “Breaking the Taboo — raising labour standards in the wine industry”. Wine Society staff apart, there were exactly as many attendees as there were panellists, 12, although 70 relevant media outlets had been invited. Taboo indeed.

The society’s in-house sustainability expert Dom de Ville kicked things off, pointing out that vineyard work is extremely seasonal and, as with most fieldwork in developed countries, doesn’t appeal to locals. When the labour force is migratory, it tends to comprise people desperate for jobs who can all too easily be exploited. Wages are low, sometimes illegally so, and working conditions often poor and even dangerous.

Not that it’s as easy as it was pre-Brexit to hire foreign labour. James Dodson runs England’s biggest vineyard management company, VineWorks. Until 2016, it relied mainly on a skilled team of Romanians. Since Brexit, however, Dodson says that “seasonal workers have to be sourced through one of five Home Office-approved agencies, but they often have little or no vineyard experience, and there is no guarantee that you will be sent the same workers throughout the job”.

He’s turning more and more to mechanisation — the most obvious solution to any labour crisis — but the rules for English traditional-method sparkling wine, which represents more than two-thirds of the wine grown in the UK, stipulate hand picking.

Anna Turrell specialises in advising big retailers on sustainability. At the start of her presentation, she called The Wine Society “brave”, to which de Ville responded afterwards by email: “How have we managed to get ourselves into a situation where we think you have to be brave to organise a panel discussion about reducing the risks workers in the wine industry face?”

One of the most interesting panel members was Allan Sichel, president of the CIVB, the generic wine body representing Bordeaux’s 4,900 producers. He pointed out that many of its members, especially smaller-scale growers, are “overwhelmed” by the myriad sustainability requirements of different buyers. “It tends to be the same stuff being presented in a different way, so a collective approach would really work,” he said.

Along with Bordeaux’s admirable environmental sustainability initiatives and generally rather lamentable financial sustainability, it seems as though it has been working unusually hard on social sustainability, improving standards for its considerable workforce (despite the inexorable move towards machine harvesting, responsible for 80 per cent of the crop in Bordeaux).

Sichel explained that growers in Bordeaux, like so many of their counterparts elsewhere, thought that if they employed a vineyard management company, of which there are more than 550 in Bordeaux, then it was that company that was entirely responsible for pay and working conditions. Not so. “Twenty years ago, we thought we were protected by social laws, but it was a few well-publicised cases by the press or whistleblowers [of worker mistreatment] which made us aware of the responsibilities of growers too,” he said. “Many of the growers are surprised that it’s up to them to be sure all the people they employ are old enough and legal, that they have decent pay and accommodation — not just a tent in the woods — and access to medical care.”

Sichel’s local préfet, the national government representative, noticed that his area, Aquitaine, had France’s highest rate of accidents at work, mainly in wine production. As a result, the préfet was instrumental in drawing up a labour charter in 2022, which so far has 67 signatories, including many vineyard management companies and producers (some of whose wines I recommend here).

New Zealand has a similar scheme that requires employers, often vineyard management companies, to provide accommodation units for their workforce, now made up substantially of Pacific Islanders.

Gonzalo Entrecanales, CEO of the particularly sustainability-conscious northern Spanish wine company Entrecanales Domecq e Hijos, made the point that, unlike clothes, wine is largely made in developed countries, so there tends to be more scrutiny. But, he observed, the wine-grape market is extremely fragmented, and the smaller growers simply don’t have the tools to understand social sustainability issues. In addition, so many consumers buy on price, without realising that if a wine is really cheap, someone is suffering — usually the agricultural worker.

Daniel Hart of UK wine importers Hatch Mansfield has a very concrete proposal to counter this, inspired by the successful launch of the Bottle Weight Accord, an agreement whereby all manner of retailers sign up to use bottles with an average weight of no more than 420g by the end of 2026. “We need a number, like we have for bottle weights, a fair price for a bottle of wine which takes away the risk of exploitation of workers,” he said. At the moment, he says, the cost of the wine itself makes up less than 10 per cent of the shelf price of the average UK bottle of wine (which would be a 13.5 per cent ABV bottle, costing £6.63). The rest is taxes, packaging, transport and retail margin. That 64p is “barely enough to ensure the ethical treatment of workers”.

Master of Wine Jo Ahearne used to be a winemaker/blender for one of Britain’s big supermarkets. She pointed out that the KPI pressures buyers are under are getting tougher and tougher. “In the places I’ve been as a blender, I’ve seen some terrible things in vineyards. The workers tend to have their own gangmaster, so you can’t talk to them directly, even if you speak their language.”

In her experience, it has been labour conditions set out in tender documents that have been most effective in encouraging suppliers to do the right thing. The powerful Nordic drinks-buying monopolies have been trailblazers in this respect, refusing to buy wine unless suppliers treat their workers well, in schemes administered by organisations such as Stronger Together, whose purpose is to address human rights issues in supply chains.

But consumers have to play their part too, Ahearne says: “[To solve this] it has to come down to people refusing to buy wine that’s too cheap.” Although she added by email later, “I don’t want people to think that merely buying more expensive wine releases anyone from the responsibility of (inadvertently) supporting bad labour practices.”

After the event, Laura Falk, who has been advising The Wine Society for the past two years, began the task of organising online training sessions in five different languages for 160 of the society’s suppliers. The idea is to explain to them how to start tackling labour issues, and the society is keen to share all this with others in the wine trade, if they can be persuaded to address them.

Bordeaux from better employers

These high-scoring, ready-to-drink fine wines are made by signatories to Bordeaux’s charter for responsible employers.

-

Ch Branas Grand Poujeaux 2015 Moulis (13%)

£294 a dozen in bond Cru World Wine -

Ch Grand Puy-Ducasse 2015 Pauillac (14%)

£58 a magnum Cuchet & Co -

Ch Canon, Croix Canon 2016 St-Émilion (14%)

£33.85 Justerini & Brooks and others -

Ch Meyney 2015 St-Estèphe (14%)

£40.20 Four Walls -

Ch Duhart Milon 2009 Pauillac (13.5%)

£89.39 Lay & Wheeler -

Ch Rauzan Ségla, Ségla 2016 Margaux (13.5%)

£95.94 four walls

What work needs doing in a vineyard?

After the harvest, leaves fall and sap stops flowing. The vine is dormant and its dry canes can be pruned at any time during an extended winter. As Gonzalo Entrecanales pointed out during the labour workshop described above, pruning has become hugely skilful now that wine production is focused on quality, rather than simply on quantity. With a few snips of their secateurs, pruners can help shape how the vine grows over the next few months and the likely crop level, which plays a crucial part in determining wine quality.

Pruning was once routinely undertaken in early winter, but now that spring frosts are increasingly common, it may be held back until the end of winter. This delays the appearance of the first buds, which can be destroyed by a particularly severe frost, shrinking and postponing the final harvest. Winter is also the time for vineyard maintenance, mending the now fully exposed posts and wires.

Once the vines have started to grow, shoots may be trimmed or tamed (another specialist job) and, come summer, some vineyards will strategically remove leaves and/or snip off excess bunches. Vines are prone to a wide range of pests and diseases so may need to be sprayed multiple times, and cover crops may need mowing.

In some areas, vines will be covered with nets to protect against birds.

Then comes the all-important grape harvest in early autumn or, increasingly, late summer. This is often back-breaking work in high temperatures, although grapes are increasingly picked at night, or just in the mornings, to keep them, and the pickers with any luck, sufficiently cool.

Tasting notes, scores and suggested drinking dates on Purple Pages of JancisRobinson.com. International stockists on Wine-searcher.com

Only 0.02 per cent of Japan wine is exported

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram